The presidential election cycle brings games of duck-duck-goose for the candidates. They have to visit just the right mix of business interests, ethnic groups, and men’s and women’s gatherings of all types. A few weeks before the 2012 vote, media headlines read “Mitt Romney Faces Tough Questions From Black Leaders.” Almost every news site had the exact same heading.

Other banners appear from time to time: “Black Leader Dies in South African Jail”… “Prominent

Black Leader Resigns”… and so on. There are always lots of “First Black Leaders” to do something. Unless you are a zealot for black advancement, these announcements fade into background static very quickly.

What makes these people “black leaders”? Is it their business sense, great social generosity, or their inspire-by-example life? It is time to ask how these black leader seats are sold. People just appear out of the vapor for annointing. Like the statistics the public is constantly fed: No one seems to personally know anyone who participates in polls, but the numbers are always there.

Defining Black Leaders

A Washington Times contributor wrote:

In the south, where the hierarchy of the plantation was still prevalent, blacks would bring their problems to someone recognized by whites as a black leader; he in turn, hat in hand, would try to convince the whites to address them. The practice was not only demeaning, but designed to serve the interests of whites.

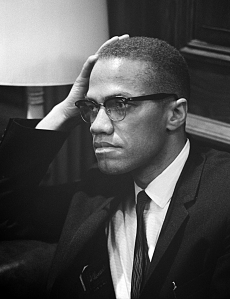

Maybe we have to raise the bar. We should ask again, if Nelson Mandela is a black leader. Bill Cosby. Louis Farrakhan. Arthur Ashe. Jesse Jackson. Frederick Douglass. This is just a fraction of the most recognizable names, always held up as symbols.

A few of these people had the mark of a true black leader. “If you are good at it, then you stand to be killed,” journalist Ralph Wiley wrote. “This is not speculation… This has been the proven course of events and goes along with the mission.”

Martin Luther King, Jr. paid this ultimate price. King is celebrated as one of the greatest humans who ever lived, though many people overlook what has come to light before and since his death. No thoughtful person denies his contribution to basic human equality, even for those who don’t agree with his nonviolent approach. Usually, King’s message is reduced to a battle for the rights of black folks, when it was much larger.

Seeing What We Believe

The effect of this perception echo today. Media, and therefore the public, appoint spokespersons. These representatives accept the call to speak for everyone who superficially resembles them. “Black people are not usually at liberty to choose their own leaders,” Wiley wrote.

Common sentiment says Dr. King was the definition of the term. It also says King was a Bible-believing Christian. After all, he was a reverend. Yet he did not believe in the divinity of Jesus, Resurrection, or the Virgin Birth, crucial points 5for a believer in Jesus Christ, so the whole assessment of King, Jr. needs a second look… one that most of us don’t want to take.

There is a sense of holding on to heroes, no matter what we look like, and no matter what they’ve done. Black Americans in particular cling to icons, harkening back to a time when society wouldn’t allow more than the occasional Joe Louis or Jackie Robinson.

This melted into what we have today, where tens of millions of people are still irrationally meant to cheer for the same guy. Even when African Americans think differently, many times they are seen by both black and white people as outcasts, eccentric, and weird. Except now there are terabytes of information to surf, and we know events going on in every town from here to Lugansk. Black leaders by someone’s definition must be a dime a dozen.

Related: Negro! Negro! Siomai & Friends Fries

Climbing Out of a Box

When African-Americans were finally free to craft parts of the world to their liking, just a few generations ago, it’s telling that a “black version” of the dominant American culture usually resulted. White America saw these derivations and picked up on the copycatting. It filtered all the way up to Madison Avenue, and media influence helped cement the separation of the cultures.

Black Jesus. Black Caesar. Hip hop artists have labeled themselves things like “Black Tony Montana” and “Black Gambino.” Sean ‘P. Diddy’ Combs was fond of calling himself the black Frank Sinatra at one time, and probably considers himself a black leader.

We have had Black Entertainment Television; black award shows; and black versions of TV commercials with different music and characters. These things are justified in the name of “we want our own.” But it comes off as diminished to all parties — again, with the exception of the progressive who thinks anything with “black” in the title or content is a good thing.

Some argue that too many black Americans view themselves as part of a separate culture, which is technically true. The fact that African Americans vote overwhelmingly Democrat, despite this political party paying only lip service to so-called black issues, is proof that a “hunker down together” mentality has stunted not only blacks but the United States.

However, that viewpoint grew out of a history of being treated as separate, unequal, and even less than fully human. People are not born into a vacuum; they are affected by the social and cultural waves that were already rolling. Our thoughts, attitudes and perceptions fall onto those that come after us. Most of us like to think of ourselves as independently-thinking intelligent beings. We don’t like to admit that what happened before us, absolutely has an effect.

All of that fits into the black leader issue. Harold Cruse wrote, “The leaders of the civil rights movement… subordinate themselves to the very cultural values of the white world that are used to negate, or deny the Negro cultural equality.”

Kevin Powell described the dissatisfaction of black Americans with “[President] Obama… the de facto leader of black America.” He agrees that the sense of missing a suitable leader stretches back to the end of the civil rights movement. As the 1980s approached, “black leadership became not only rooted in racial protest, but unable to be self-reflective or self-critical,” Powell wrote.

Critical thinking should be applied before the title of leader is handed out. These days when an African-American is cast as a leader, it’s certain he or she won’t go too far “out of bounds” with the opinions.

The strata of black life in the United States, though unnoticed by the casual glance, ensures that no one can speak for all. This is an obvious statement, but people of every color, nationality, class and intelligence level have willfully forgotten.

Cruse, Harold. The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual. Apollo Editions. 1967.

Wiley, Ralph. Why Black People Tend To Shout. Penguin Books. 1991.

[Originally published March 2014]